What Working Class?

The breast beating of post-election blues therapy once again confesses to sins of omission in the department of let’s understand the working class. What are you talking about?

The Flyover Country was in open rebellion on November 5, 2024. Again.

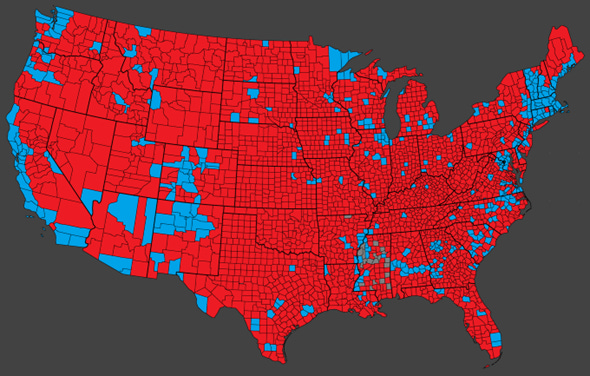

A similar picture had emerged in 2016 already, but this time the electoral results by county reveal a truth so clear that it must make Democratic strategists curse the invention of the jumbo jet and Jimmy Carter’s Airline Deregulation Act of 1978. Just look at the map below.

The presidential election of 2024, results by county. Liberals are now confined to reservations, making it easier for labor to study their language, traditions, rituals, and semiotic environments.

The most recent election gives new meaning to the term Flyover Country. Often used in a pejorative way, the term now has a fair chance of being elevated to epistemological heaven as Democrats continue to ponder the two main reasons for being grounded yet again. Flights are canceled most often because of inclement weather or striking workers. That must be why Democratic voters this time around were confined to counties within easy driving distance of the nearest international airport (find your city on the map above and you know what I am talking about). General weather conditions were poor, politically speaking, and yes, the workers were on strike, unwilling to deliver.

Now, before we metaphorically turn to matters of meteorological wisdom and labor pangs in the Harris-Walz camp, we should point out the exceptions to the rule of Democratic voters staying close to the getaway hubs of America: Indian Reservations. Native Americans were forced to settle far away from railroads in the 19th century and in today’s Reservations they are no closer to the blessings of modern life than they were when the frontier closed in 1890, as Frederick Jackson Turner pointed out in 1893. Yet, the people of Pine Ridge, Standing Rock, Rosebud, and elsewhere tended to side with Kamala Harris, though not always, and it appears that lands ceded to white settlers as a result of the Dawes Act of 1887, though technically still Reservation country, are now inhabited by Trump followers. Native Americans, if the map above is any guide, prove the point that proximity to a busy airport is not a precondition for seeing in Democratic politicians the more likely champions of uninterrupted federal cash flow.

The similarities between the Indian Reservation and the Urban Ghetto, therefore, cannot be the means of travel, but the means of production. If you cannot get away to Aruba at the drop of your credit card, it does not matter whether you live on Pine Ridge or at the end of the runway of Chicago’s Midway International Airport. Semantically, we should admit we have a de facto reservation system going on in urban America that keeps people in their place even where the fuselage to freedom appears close overhead, seemingly just within arm’s reach against the blue sky above.

The Flyover Country gets its name from the people crossing the continent from Boswash to Sansan at 30’000 feet, looking out of pressurized cabin windows, sipping California Chardonnay at extra charge, and seeing nothing. The Flyover Country also gets its name from people looking up, marveling at barely visible aluminum needles knitting a cobweb of white vapor trails against the blue of a virgin sky. Some Pig!

Pardon my poetry, but this is an essay I have been wanting to write for a long time. Before the election, years earlier, 50 years ago in fact, a Greyhound bus delivered me and a 44 lbs suitcase to a bus depot in the heart of America after a 36-hour journey from JFK International Airport, NYC to Fargo, ND. After another 100 miles in the family car, we arrived in rural, small-town America, population 563, and I fell in love with it. I had been raised in a more urban setting in Switzerland and enjoyed spending vacation time with my maternal grandparents who were dairy farmers in the Alps. But the Prairie was a revelation. It offered vistas far beyond what I had been used to. I learned that the three-dimensional qualities in life are not necessarily evidenced by the imperative of an up-down landscape.

There were visible cracks in the country then. Within 48 hours of arriving in rural America, I realized there were two things I should not ever talk about: Vietnam and abortion. The Supreme Court had reached its Roe v. Wade decision just a year earlier and a Watergate-shaken country was in the process of extracting itself from the trauma Southeast Asia had become, pulling out completely by April 30, 1975. Shame, anger, and lost innocence accompanied these developments that few had foreseen and fewer yet had wished for. Alienation is the main ingredient in fomenting political change, and it would come within just a few years.

Things that do not get talked about openly have a way of germinating underground first, gaining strength, deepening roots until moisture, temperature, and sunlight create the perfect conditions for a good crop. People in rural America talk about the weather incessantly. It is easily their number one topic, followed by the price of gas. They know that not everything they wish and hope for is the result of their own doing. It takes patience, often lots of prayer, and faith in providence until giant machines can be sent out to comb the land to harvest the vast colorful carpets of wheat, barley, oats, corn, sunflowers, soybeans, alfalfa, potatoes, and sugar beets.

Democrats were still in charge in that part of the country then. Bob Bergland, wheat farmer, was the U.S. Representative for Minnesota’s 7th Congressional District which runs north-south along the border to the Dakotas. He became Jimmy Carter’s Secretary of Agriculture in 1977. Across the Red River of the North, Quentin N. Burdick was North Dakota’s longest serving U.S. senator. When I met him in 1981, the Democrats of that State had been sending him to Washington since 1958 and would elect him twice more, in 1982 and 1988. He was an amiable man, with a background in farming and a law degree which he had put to good use representing farmers threatened with foreclosure during the Great Depression. Every 4th of July we would fly the flag that had been flown over the U.S. Capitol and which the Senator had given to my father-in-law, a Republican, for generous campaign contributions to the Democrat’s many reelection efforts.

But things, they were a changing. Through the eyes of the newly arrived foreign student, rural America was a different planet from that portrayed in movies made in U.S.A., and it would have been a jarring experience had it not been for the incredible generosity and warmth of the family and the whole town. Poverty was palpable but not oppressing. Farmers were struggling and of those I knew, within a few years many gave up. All the while I was wondering what in the world those giant B52s were doing over there, in Vietnam, dropping more than five million tons of explosive, incendiary, and chemical ordnance mostly on rural areas in a strategy called carpet bombing. It was more than twice as much tonnage as the U.S. had dropped in all of World War Two. Meanwhile, retrenchment drained funds from badly needed investments in schools, health care, housing, and a ton of other projects at home, in Flyover Country.

Rural areas around the world are suffering from governmental neglect. I have seen it in Italy, France, Germany, and Tanzania. The current political shifts in those countries are in part due to the structural crises engulfing people in remote areas and their own version of alienation. But the urban-rural divide in the United States feels different. Much of it has to do with the history of farmers and workers in America, their struggle to be heard, and the experience that in times of national emergency, such as great wars, esteem and even reverence for the hard-working men and women in factories and fields tend to be up – only to be cast off when national emergencies subside. It took World War Two to bring electricity to rural U.S.A. and it comes as no surprise that the arts rise to their best then also, paying visual and audible homage to those who pay the ultimate price in the country’s struggles. Aaron Copland’s 1942 Fanfare to the Common Man with its hauntingly beautiful and solemn brass melody comes to mind, a timeless tribute to the simple folks that make America truly great.

But then, when it’s back to normal, rural Americans are reminded that Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of the yeoman farmer is largely at odds with the demands of a globalized ag economy driven by corporate interests concentrated as it were in air-conditioned office towers in faraway cities. Whereas in the legacy of Jefferson and Andrew Jackson farmers constituted something of an ideological backbone of American political consciousness, the late 20th century version of farmer-labor self-awareness seemed irreparably fractured and much less tied to the Nation’s reservoir of fast eroding republican virtues. The farm population has seen a steady decline from a peak in 1917, the year the U.S. entered World War One, and further productivity gains after the World War Two caused it to drop even further from about 20 million in 1950 to less than 5 million people today. The number of farms peaked in the mid-1930, at close to 7 million, with a rapid drop in the 1950s and 60s, levelling off in the 1990s at just over 2 million farms. Note that the ratio of people to farms declined also, reflecting an overall trend to raising smaller families.

It is that latter fact that compounds the effect of the decreasing number of farms and which ripples across the landscape of the Great Plains. As people move to the cities, many stores, schools, and churches close for good. Often, the only new buildings you see on the Prairie are nursing homes. Young people go off to college, never to return. They do come back to visit, some with shiny cars and fancy degrees, speaking in academic tongues and reinterpreting the world to mom and dad, grandma and grandpa, aunts, and uncles. That is about the last thing they want to hear, further adding to their alienation which hurts even more because it comes from their own flesh.

1st Street, Girard, IL: visualizing the need for progressive bathroom legislation

The political fallout came against a backdrop of earlier developments that already contained the seeds of discontent. The Farmer Labor Party (FLP) had been a highly successful political force in Minnesota during the first decades of the 20th century. Farmers and urban labor were united in their perception of a system rigged in favor of banks and big money interests in general. Farmers wanted easy credit and price stability whereas labor wanted safeguards against the hardships of economic downturns. With full employment during World War Two, one of the most successful third-party movements in U.S. history saw its reason for being eroding fast. Enter Hubert H. Humphrey who merged the State’s smaller Democratic Party, largely the political home of U of M academics, with the FLP in 1944. The Minnesota DFL Party is now 80 years old, but the internal schisms not only remain, they have become more pronounced in a nationwide trend that saw union membership drop, farmers either quitting or turning corporate, and academics pursuing their own bubble agenda.

3rd Street, Mott, ND: CLOSED. Where “Even Cowgirls get the Blues” (Tom Robbins)

If rural America suffered an erosion of political clout after World War Two, as we have seen, then labor downright collapsed. The number of workers organized in unions saw a drop from 17.7 million in 1983 to 14.3 million in 2022, which in a growing population meant a whopping decline from 20.1% to 10.1% during the same time span. The United States had the fifth lowest labor union density of the 36 OECD member nations in 2016.

The history of labor in the United States is as colorful as it is painful. Much of it has to do with the specific American elements that set it apart from, say, European labor movements from the outset of the industrial revolution to the present. I see five reasons that have defined and hampered labor’s struggle to become politically relevant at an institutional level in the United States:

1. Immigration

2. Slavery

3. Republican form of government

4. Normative biases

5. Voting laws

The United States enjoyed a steady inflow of labor mostly from Europe. More than 34 million migrated from Europe to America between 1820 and 1957, often bringing with them valuable skills but low political ambition (the Germans here being somewhat of an exception until World War One). By and large, immigrants aspired to advance socially and economically in America rather than cementing their status within the rigid strata of a labor classes.

When slavery was abolished in 1865, hard labor in factories and fields remained the often only option for unskilled blacks. Their ability to organize was actively suppressed by employers and further impeded by the lack of organizational experience and little formal education – which was often discouraged and even thwarted. Slavery also had a halo effect on wage earners in similar lines of work, associating manual labor with an undesirable existence and as something to overcome rather than master. Much of that corrosive normative framework persists to this day as evidenced by a strong bias against organized labor from within labor itself.

Shame, not pride, taints any attempt to cultivate some sort of working-class consciousness in the United States. The country’s republican ethos taps into notions of equality and individual rights rather than the very real layers of social and economic inequality that form the backdrop of everyday experience for all Americans. Republics, such as the United States or Switzerland, are less inclined than monarchies (or former monarchies) to accept social stratification as immutable and natural even if social mobility remains in fact unattainable.

Add to the above voting laws that have all but crippled repeated attempts to give labor a political voice in U.S. politics. It is structurally nearly impossible to garner enough worker clout into a single party as the two-party system resulting from majority voting rather than at-large elections logically marginalizes not just workers but all group interests that do not neatly fit into either of the two major parties.

There is an obvious lesson in this that once again eluded Democratic strategists in 2024: It makes no sense to court fringe interests at the expense of alienating your main constituency. Elections are won by majorities after all and reaching out to the edges may be morally uplifting but tactically unsound. Even worse are the sins of declaring your main constituency to be the new fringe strategically while pulling side interests to the core and anointing them with the oil of infallible elite doctrine.

The uneasy alliance between Democratic academics, labor, and farmers in 1944 would eventually provide an opening for Republicans who aimed squarely at what really counted in Flyover America: Family, Church, and Country. Go against any of these, and you will lose. I heard it said for the first time in the late 70s that people would rather vote for a potted plant than for any pro-choice politician, regardless of party affiliation. At about the same time, politicians in these parts would privately admit to being pro-choice but espousing a pro-life stance publicly to have any chance of being (re-) elected at all.

The presidential election of 1980 became an inflection point. Ronald Reagan, a moderate anti-abortion politician, tapped into the anger and shame of the late 70s. He understood that the Flyover Country was a massive reservoir of moral might much stronger than the parochial look-at-me posturing of group interests. His determined call for the rebuilding of U.S. military strength after the humiliating loss of Vietnam and the Iran debacle had a much stronger appeal than Ag Secretary Bob Bergland’s careful analysis of what really ailed the American farmer. Reagan promised a navy of 600 ships, imagine that, echoing Theodore Roosevelt’s naval build-up of times long gone but whose memories lingered on in the names of the battle ships christened after Prairie States: Iowa, Missouri, Indiana – all of them not just place names but indelible pillars of pride in the history of U.S. imperial greatness, inseparable from the sacrifice made by the men called to duty away from America’s heartland.

Reagan knew he could largely ignore farmer and labor interests, and get away with it if he upheld the triad of Family, Church, and Country. When about 13,000 air traffic controllers walked off the job on August 3, 1981, President Ronald Reagan gave them 48 hours to return to work or forfeit their jobs. The Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) was one of the few unions that had endorsed Reagan in 1980. Their strike for higher pay and better working conditions was illegal and likely could have been averted under more favorable circumstances. But it gave the President an opening during his first year in office to show the country once and for all that organized labor had lost its clout politically and culturally. The working class had become something of an academic interest to be studied by armies of sociologists but definitively ceased to be a self-ascribed moniker of any political relevance to the millions of Americans dependent on fair wages and safe working conditions. When striking air traffic controllers were shown on television being led into court, arraigned before a federal judge in handcuffs and chains, it was a humiliating moment in American labor history. The old shame sticking to blue collar work in America became ever more embarrassing and effectively crippled further efforts to galvanize labor as a politically relevant force, instead moving it to the fringes where – as we have seen – you don’t want to be if your aim is to win elections.

In 1984, Reagan ran for re-election on the slogan "Prouder, Stronger, Better." The television ad campaign featured the opening line "It's morning again in America" and if that sounds a lot like MAGA in 2024 to today’s ears, it would be hard to argue that it wasn’t so. Reagan the actor knew intuitively that a good story is infinitely more important than hard facts, and the story does not even have to be true. Facts are for nerds; stories are for the masses of people yearning to be understood.

After 1979, American workers no longer participated in the gains of productivity. Real wages began to stagnate. More and more families were forced to rely on two incomes to make ends meet thus compounding the problem of a ballooning labor supply while driving down demand and with it the cost of hiring them. Since 1980 productivity rose four times faster than wages paid.

The shaming of the American worker and farmer has continued since Reagan made it even more acceptable than it had been already. As I have pointed out in an earlier essay, both Harris and Trump made half-hearted attempts to court the working class during their campaigns. In part, the muted effort was due to the desolate state of labor as discussed above, its hopeless fragmentation, and its disavowal by the working class itself. Worse yet, both candidates signaled strongly that the fate of the working class was just that, fate, something to overcome perhaps, but not the honorable stuff of political consciousness raising. Labor would never be the starting point of political coalition building in an economy that had undergone deep structural changes and in a culture that had never in its history taken labor seriously – except, remember, in times of national emergency. Harris knew it, “forgetting” her stint at McDonald’s, and Trump knew it, mocking not just Harris but all those men and women who make a living in the fast lane of American life, feeding the folks on the run.

Seen this way, gaining the support of those we might objectively call the working class becomes not a matter of addressing bread-and-butter issues, but a matter of telling the better story. And every good story has a moral to it; a teaching point that may be uplifting or confirming one’s fears, hopes, and values of the heart. Never mind that such are the conditions that open the gates to demagogues who cynically exploit people’s tacit acknowledgement that they are relegated to the fringes, powerless, alienated from the center, but eager to be heard, if not understood. But it could be an opportunity, too. Instead of catering to fringe groups clamoring for their conspicuous consumption moment it would be more honest to descend into the substance of political moving moments in Flyover Country. Instead of giving in to the temptations of moral and intellectual resignation by proffering Potemkin-like life-is-wonderful-solutions at mega concerts it might be useful to get your hands dirty on the farm or in the factory. Instead of subtly pronouncing let-them-eat-cake elitism to be morally relevant it might be more promising to try connecting the dots between bread-and-butter concerns and dysfunctional morality.

What we have seen amounts to sustaining Antonio Gramsci’s keen observation (which did not earn him any credits among his Marxist followers in the 1920s) that the working class often blocks its own progress towards economic justice and social clout. Workers inadvertently hobble civil society’s potential means of organizing and communicating effectively by espousing detrimental values. In other words, applauding the country’s naval build up will perhaps make you feel good but you can be sure it will cost you dearly. Cheering high tariffs may emotionally feel like Hollywood style revenge but you will get the bill at the cash register over and over again.

The Flyover Country has spoken. The next time you board an airplane from JFK to LAX it might occur to you that you buckle up America’s working class into your seat with you. Thousands of people make your flight safe and enjoyable. And as you look out the window to the fields and farms 30’000 feet below, ponder the journey of the sandwich in front of you. Also think about the folks down there whom you cannot see but who look up at you, perhaps, just perhaps, murmuring something like: Some Pig!

Do we see the irony in today’s political discourse? Are we willing to see it?