Preface

Hello and welcome to my little growing Substack community. A special warm welcome to my faithful readers and subscribers. And a big thank you to my paying subscribers who help me buy coffee and such.

Some of you may have noticed that I started a Substack in German. About one third of my subscribers are German speakers and many of them are also fluent in English. I thought it would be nice to branch out and post something in German on occasion. Writing in German would also allow me to cover topics that would be of special interest to them.

Simply translating posts will not work. Instead, I will continue to write in English and German, but not necessarily always about the same thing. If you are fluent in both languages, please subscribe to both newsletters to get the whole story.

The Language of Democracy

A few days ago, I posted an essay on the language of democracy in German. As our German neighbors get ready to head to the polls on February 23, it seemed like a timely topic. I have followed political debates in Germany for decades and always thought that the Germans struggle with their own language and its possibilities when it came to articulate notions of democracy and freedom. To an outsider, the debates in the Bundestag are sometimes hard to take. The rants about real and alleged failures attributed to the opposition often show a chilling malice both in content and form, frequently made more sinister by the speaker’s use of body language reminiscent of the chamber’s darkest hours.

In my German essay, I looked at some of the patterns in Germany’s political discourse and its specific use of certain key words and phrases. It may be self-evident that our language and especially our use (or abuse) of it shape our political awareness. But we tend to avoid any causal link between the idioms we choose and the political biosphere we call home because acknowledging the constraints of language tugs at our desire to control our convictions. Anyone who is familiar with a foreign language, however, will immediately understand that one’s own mother tongue is but a comfortable prison.

In the German context, as I have argued before, the more recent tortuous past of two dictatorships within the span of three generations has certainly left its scars not only on how the Germans speak to each other politically but also what they consider to be the legitimate parameters of political debate. In truth, however, the parameters on the political imagination and its articulation have much deeper roots that extend into the Middle Ages when the basic fault lines within German public discourse first emerged. The near constant struggle between the emperor and his distractors could in fact be traced to the Investiture Controversy between Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV in the 11th century already, a dispute that lingered on long past its formal resolution and formed the basic political backdrop of the Reformation in the early 16th century. The world, far beyond Germany, has not been the same since and the fierce struggles that have resulted from the upheavals of the early modern era left deep scars in the German psyche and therefore its language as well.

Luther’s translation of the Bible lay the foundation of what would become standard German, the language of poets, scientists, and bureaucrats in a large swath of Europe. But it would also become the language of a new political awareness, sometimes yearning for freedom, and sometimes deriding those pushed to the fringes of society. The evolution of standard German coincided with the rapid proliferation of the printing press. In fact, it is hard to conceive of a standardized written language anywhere without its mechanical multipliers and millions of people adhering to its canon of grammar and syntax.

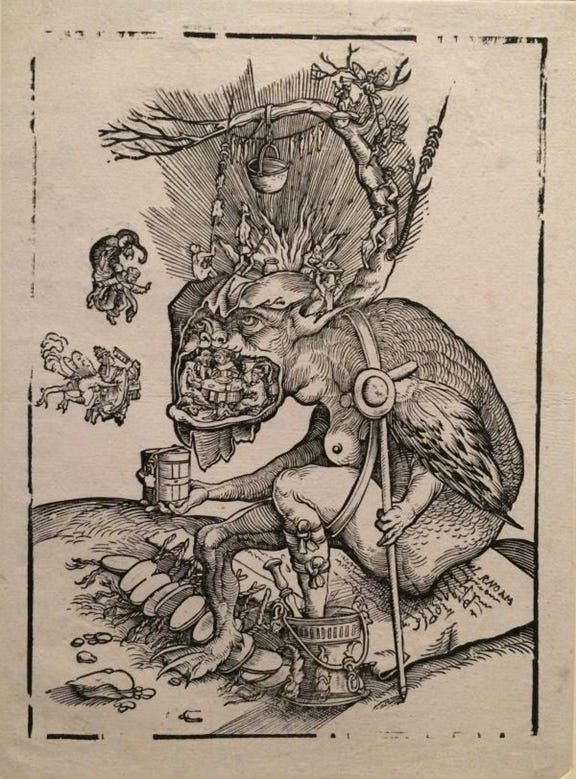

But along with the spread of standards, there came the proliferation of ideas. The Word of God and the demonization of thy neighbor went hand in hand, carried forth into the vast woods of middle Germany to spread both hope and fear. Adhering to one set of beliefs, fueled by hellish cartoons and poisoned pens, could expose you to torture and death at the hands of those opposed to you.

Matthias Gerung, Satire of Indulgences, before 1536, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett

It is well documented that Luther’s own insistence that he would not recant any of his 95 theses led to a radicalization of public discourse in Europe, on all sides, as his “here I stand and can do no other” (1521) found innumerable imitators of all ideological hues. His famous words echoed throughout Germany’s own phase of empire building in the 19th century and became the phrase of spiteful, defiant spouters in many variants during the Second and Third Reich. It is part of the political rant in Germany still and these days especially in the context of maintaining the Brandmauer, the ideological firewall many especially on the left consider essential to keep ostensible trouble at bay – and themselves in the power game.

The refusal to dialogue, therefore, is clearly not new in Germany. Nor, to be fair, is it exclusively German. But Carl Schmitt, Germany’s enduring bad boy political philosopher picked up exactly on that Hegelian notion of antithetical exclusion when he insisted that the political world necessarily and naturally presents itself as an enemy-friend dichotomy.

I admit to a sinking heart feeling when I watch Germans across the Rhine getting ready to cast what might once again be a historic vote in the monumental sense of the word. The us-versus-them claptrap permeates political debates on TV, radio, social media, bill boards, and the printed press. Shouting matches replace what in a republican setting should be civilized discourse and reasoned debate.

Enter J.D. Vance. Last week, the U.S. Vice President added fuel to the fire. While in Munich (of all places, for heaven’s sake!) he lectured his mostly European audience about freedom of speech and the dangers to democracy from within. What could have been a great speech, drawing from the finest in American oratory tradition, landed on the airwaves like a cynical slap in the face. The reason, it seems to me, were not the shared values to which he alluded, but the hypocrisy of context. It is simply not possible to pretend that your audience was unaware of the speaker’s own sins in the department of election fraud, the manipulation of the courts, and the suppression of free speech.

His language was not vulgar or rude. His English was polished, refined, smart. When he set out to talk about the dangers to democracy from within, my immediate thought was of Lincoln who said the same thing in 1838. But I quickly realized that Vance was no Lincoln when the current VP, unlike his great GOP ancestor, offered no solutions and no forward-looking vistas of how to save democracy from the enemies within its own borders – and indeed from within the heart of each citizen. When the man of Hill Billy Elegy fame set out to plead for more democracy and self-determination, I thought for a moment – hope against hope —that he would reverse the administration’s sneak preview of Ukraine’s undoing by declaring something statesman-like such as: “The United States has always espoused the principles of self-rule, democracy, sovereignty, and freedom. The United States sacrificed hundreds of thousands of soldiers on European soil to establish and defend freedom. Now is not the time to give up or give in to the forces of evil.”

It could have been J.D. Vance’s finest hour, a thunderous debut on the European stage of international diplomacy, an excellent opportunity to ban the ghosts of Munich past. But it was not. Instead, what we got was an embarrassing dud.

The language of democracy, which is the language of some of the greatest defenders of freedom such as Lincoln, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Kennedy, was now used to tell Ukrainians that their freedom was not worth fighting for, that the horrendous sacrifices they have already made were in vain – and had better not been made.

Yes, of course, we are all in favor of honoring the will of the people, free speech, and respecting constituencies, but we would like to see the same principles applied everywhere, in Europe, the United States, and Ukraine. (Russia? Keep dreaming!) Vance’s implicit assumption that his audience would somehow have a mental blackout when it came to assessing the health of American democracy made him appear naïve und inexperienced. Clearly, Munich, Bavaria is not Toledo, Ohio.

The international stage is not a Hill Billy café. You cannot sit down at the counter and order a mug of coffee in polished English and hope people will not laugh in your face.

If you make use of the language of democracy, you must deliver. Your credibility is on the line. Your audience is listening, wants to listen, wants to believe you. They want you to put your money where your mouth is. They will never forgive you if you bandy grand ideas and then spill coffee in your lap.

The damage is two-fold. Vance and his idiosyncratic look-at-me government have turned their back on a country’s struggle for freedom. That by itself is unforgiveable. But I wonder if the long-term damage from ruining the language of democracy may not be worse, far worse. Political parties and pundits in pre-election Germany have either been confirmed in their anti-American stance that has been part of their political DNA for decades or they have been confirmed in their barely concealed contempt for democratic republicanism.

There is much talk about re-arming Europe. It is an eleventh-hour attempt to make up for what might be America’s turning her back on Europe altogether or cutting back her commitments significantly.

But the military effort may be no more than treading water if there is no revival of a democratic language. The Germans do not have a language at their disposal that lends itself to encompassing visions of democracy across the European spectrum. The Germans with their Carl Schmitt infested dichotomy view of politics are about as suitable to republican democracy as the Swiss would be to reinventing monarchy (please spare us!).

If American leadership goes missing, it will be the language of democracy that will be missed in the long term, not the military hardware. The Germans are good at building tanks and howitzers, and with a bit of political daring, they will crank them out again in short order and in large numbers. They will even teach their young men to march again and salute smartly.

But who will teach them the language of democracy? Who will teach them the finer points of Lincoln’s great speech of 1838 in which he not only identified the enemies of democracy within but also how to combat them?

The question at hand is awkwardly obvious: What good does military build up do, if your democracy is weak or even at the risk of falling apart even before the first shot is fired?

For that reason, I wish Europeans had listened to Vance more closely before debunking him as irrelevant. The salient points were his, but he spoiled the message by not backing his words with credible action or the promise thereof. Instead, he just walked away.

Now, Europeans are scrambling. Their immediate response is focused on military defense. But soon they will discover that men in uniforms have hearts, too, and they need to be won to a cause worth fighting for.

But right now, there is an eerie silence in the European democratic theatre. The language of democracy has gone missing.

********************