One Seventh of a President

The Executive Branch Needs an Overhaul, in the United States and elsewhere.

Martin Pfister taking his oath of office after being elected to the Swiss Federal Council, March 12, 2025

The two chambers of the Swiss parliament, acting as the electoral college in accordance with the Federal Constitution, reached a decision in only two rounds of voting. After Viola Amherd had resigned in January, the election to replace her on the seven member Federal Council, the country’s executive branch, was scheduled for March 12, 2025. Martin Pfister, who received 134 of 245 votes cast, took his oath of office immediately upon being elected and then posed for pictures flanked by two young women from his hometown in traditional dress. Notice the flowers. Nothing of importance ever happens in Switzerland without beautiful bouquets of flowers.

The routine event did not make waves. That is, it made little waves in Switzerland, which I think is appropriate for a landlocked country. There were only two official candidates and both deemed qualified for the highest office in the land, but some felt there should have been a larger field of contenders and that caused journalists to speculate about the attractions and burdens of the office. Well, well.

But it was largely ignored abroad. And that, let me tell you, is a good thing. Foreign visitors often apologize for now knowing “who the Swiss president” is. No need to apologize, I tell them, because that is how things are meant to be. Power is precious, and it belongs to the people, first and foremost. It is delegated sparsely and then limited further by having to answer to the people and to the parliament. Those elected to the executive branch, the most visible of the three branches of government, are called to serve in a spirit of humility and cooperation, perhaps the two most important traits required of those in high office in Switzerland (and not just at the federal level, incidentally).

The tie-breaking vote belongs to the President, so-called, who has no additional powers and serves only a one-year term, from January 1st to December 31st (currently Karin Keller-Sutter, in case you need to know).

The idea of sharing power in the executive branch is of course not new, nor uniquely Swiss. It suits the Swiss, though, who never had a king of their own, and cannot imagine having one, or someone like him, to lord over them. They had ruled themselves for more than five centuries through a maze of treaties, much like the EU today, and with the dawn of the modern era came around to the idea of giving themselves a Constitution. That did not happen easily. It took a brief civil war lasting three weeks and five days, and taking the lives of 177 soldiers.

That was in 1847. Only one year later, the Swiss adopted their Constitution. They were able to act quickly because they cheated, at least a little bit. The Swiss framers of the Constitution were smart enough to realize that they could not do all the heavy intellectual lifting themselves. The only other republic with a working democratic framework at the time was the United States, and James Madison, John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton had laid out all the reasons why the U.S. Constitution was worthy of being copied, at least partially. The Swiss liked the federal framework, the bi-cameral legislature, the checks-and-balances, and the Bill of Rights.

Now, the advantage of copying something good is that you can improve on it. In 1848 the Swiss benefitted enormously by looking across the Atlantic for inspiration and just across the Rhine in horror where the Germans were busy repressing republican uprisings and reinforcing monarchic rule. An estimated 40,000 German republicans fled – you guess it – to the United States and Switzerland in about equal numbers to the great benefit of the only committed republics at the time who took them in. That was the backdrop against which it became imperative for the Swiss to avoid anything smacking of monarchy, eschewing even the left-over trappings of the British monarchy so evident in the U.S. Constitution.

Article II of the American Constitution calling for a president and vice president appeared to violate just about every republican principle the Swiss cherished. That one man (no woman yet in the U.S.) should have so much power was simply inconceivable to the people of a small country made up of many ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups.

In truth, the American framers of the Constitution who gathered in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to discuss Article II, went to great ends to avoid the trappings of monarchy and what they felt would naturally flow from it: tyranny. They, like the Swiss, even avoided the language of the monarchs, renaming ministers secretaries, for example. The men gathered in Philadelphia even considered the election of three men to the executive office, but in deference to George Washington who was set to be elected to the highest office, felt they could not put anyone with equal power at his side.

That was a big mistake. Take it from Warren Buffet; never make institutional decision based on personal preferences. People come and go, but constitutions are meant to lend stability and guidance beyond the whims of time.

I think the U.S. missed a great opportunity back then, in 1787. It failed in distancing itself as radically as it should have from Britain. Many of the institutional and cultural biases well beyond the political framework remained British. The colonial population had been raised in a monarchy and despite the revolutionary spirit seeping through the colonies, people also wanted continuity and familiarity.

Given the history, it comes as no surprise that the current resident at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue sees himself as a king, an important king, and millions of his constituents (subjects?) agree, applauding. Disgusting. But it was bound to happen. The seeds for someone to come along to abuse and pervert the office were there in the setup of the office itself.

Like the kings of medieval Europe, the U.S. president is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and has the power to pardon those convicted of crimes in a court of law. He can appoint judges and cabinet members, requiring only a majority of the Senate to confirm his choices. In theory, his power is limited by the legislative and judicial branches of government, but if they are put there to do his bidding in the first place, the mechanics of checks-and-balances break down fast, as we have been witnessing in recent months. The compounding effect of having only two parties in power hugely increases the risk of razor thin majorities pushing ideological power games rather than seeking compromise or consensus (most modern democracies have given up majority voting in favor of proportionate voting to ensure better representation of the people). The effect of such a constellation is obvious: A near gridlocked legislature will defer to the executive branch and if that office happens to be occupied by a moral weakling, catastrophe is pre-programmed. The institutional guardrails simply are not there or do not work as intended. The legislature loses despite itself and in the process the executive branch is inflated.

The current constitutional crisis in the United States in part reflects the changing role of the executive branch elsewhere. Presidents in many countries have accumulated more power over the last decades and now threaten to unbalance the sharing of power in democracies and in some cases turning to authoritarian rule outright even if democratically elected. Viktor Orban of Hungary and Recep Erdogan of Turkey come to mind in Europe while in the United States of America D.J. Trump makes no secret of his admiration for the dictators and near-dictators of this world. His playbook is, alas, typical of tyrants past and present; ignoring both the courts and the legislatures will tell us all we need to know about the decline of republican democracy.

Lord Acton, the famous British historian (1831-1902) said it bluntly: Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Give them an inch, and they will take the whole nine yards. Trump is not the first president to grab more of the already vast powers granted to the executive branch under Article II of the U.S. Constitution. Others before him, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Lyndon Johnson, to name just three prominent American presidents, have in their own way stretched and sometimes tested the limits of the prerogatives of the executive office. But unlike D.J. Trump, they never questioned the guiding principles of American democracy such as the rule of law and the wisdom of checks-and-balances.

Yet, the roots of the current malaise run deep. They are not just institutional, by design as it were, but cultural.

Take the presidency again. On my first visit to a USDA office in rural Minnesota in 1974, I experienced something far more unsettling than culture shock. There hung, can you believe it, behind the desk of these dedicated, competent, and hard working federal civil service workers the portrait of Gerald Ford who had just assumed the presidency on August 9th that year after Richard Nixon had left the White House in disgrace.

I had never seen anything like it. Obviously, Ford’s picture hung there because it had to be that way. It was not because the civil service employees took a vote and decided to replace aunt Mabel and the grandkids with the POTUS. This was far more sinister. I think it meant to show who’s boss. Worse, it meant to signal that the people working there saw it that way, too. Of course, I did not say anything at that time. I kept quiet because I knew that culture is culture and as such non-negotiable. But I was deeply disturbed and my intuition told me that it would not end well.

If they can put up the portrait of a nice guy, such as Ford certainly was, they will not refrain from nailing the mug of an idiot on the wall, if elected. It was just going to be a matter of time.

Seeing Ford, the president, framed on an office wall in a simple Prairie office building went against the grain of everything I had been taught. It violated not only my Swiss republican sensibilities, but also Commandments I, II, and III. It seemed downright blasphemous to idolize someone you had elected to serve. To serve! Not to lord over you.

In short, I had an early sense that Americans made far too much of the presidency. Presidents everywhere, and they have their own holiday, too, as if they were some saints, collectively. Then they have their monuments and in South Dakota they took a perfectly fine mountain, and ruined it by carving the faces of four of them into what would have been a holy site to the Native Americans. And you could not buy a can of soda without paying for it with coins or bills reminding you of Article II of the U.S. Constitution. Parks, streets, buildings, universities, even entire cities, counties, and a state named after presidents. No wonder it gets to their heads.

It’s too much. Things are destined to get out of hand. We should have known that something was not quite right when Andrew Jackson, president from 1829 to 1837, reportedly spent an inordinate amount of time sitting for portraits, just before the daguerreotype was invented. He was the first president to actively promote the dissemination of his portrait – clearly not a good omen.

Jackson looms large in the gallery of American presidents. Few have been as controversial as he. Many see in him the beginning of a populist streak in American politics, including all the racial overtones. Some mocked him as King Andrew the First, an obvious acknowledgement of Jackson’s authoritarian bent and his thirst for expanded executive power. Yet, the common white man loved him and his portrait could be found in many a simple frontier cabin.

Non-whites had no reasons to like Jackson. He was adamantly pro-slavery and his Indian Removal Act of 1830 made him ever more popular with white settlers but cost the lives of thousands of Native Americans who had to relocate to lands west of the Mississippi river in one of the saddest chapters in U.S. history.

There is something repugnant about presidents celebrating themselves and deporting the people they do not like at the same time.

The other day, D.J. (dance-to-my-tune) Trump visited the Department of Justice to deliver much venom of vengeance and grievance. Media outlets showed him arriving at the offices together with Madame Pam Bondi, his do-it-for-me at the DoJ. And there it was again, just above the door, the sinister image of the man just entering through the door below. There is no point in showing it here; I hesitate to name an illness by creating more of it.

The crisis in American government is not the failure of the Democrats to win the hearts of enough people or the Republicans shuttering the hearts of some of the people. The moment of truth in American democracy has arrived at the feet of the very foundation of its institutions. It must be back to the drawing board for the best and brightest of American thinkers. Americans, muster the courage and wisdom to reform your Constitution as the framers 238 years ago said it should be reformed from time to time. Amendments will not do now. All three branches of government need to be modified, some of them radically, and the Article II most radically so.

Also, start taking down those portraits. Blow up Mount Rushmore. Flatten the Lincoln Memorial; Abraham Lincoln would have never approved of it himself anyway. Rename your parks and cities.

Then focus on issues, not on heads. Start talking to one another about how to improve the lives of Americans and not about whom to follow. Elect humble people, not those who refuse to take public transportation.

Think Republic, not Monarchy, not Despotism, not Tyranny.

Reflect on republican virtues. What can I do for my country? My neighbor, my town, my state, my school. None of these actions require a president. Presidents will stop being important. The Republic will flourish again. That is far different from making it great again, and far better.

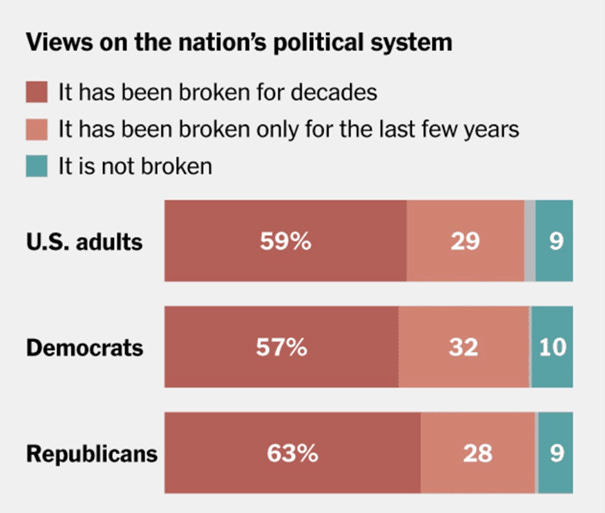

A recent survey by the New York Times showed Americans’ view of the political system.

There is a call to action in these findings.

Dismantling the power of the presidency is the most important step. After more than 250 years, it is time to get rid of the last vestiges of British monarchy and reconfigure the executive branch to reflect the American experience and the best aspects of its unique republican democracy.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025_Swiss_Federal_Council_election

https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderbund_War

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Fifth-Republic-French-history